As I write this, the Monaco Grand Prix is on in the background. It is one of those sporting events that inspires awe, as the maximum performance of these engineering marvels is extracted with millimetric perfection from the drivers.

The streets of Monte Carlo first became a circuit almost a century ago (1929) and lap times were over a minute slower then; this is equivalent to years in the world of motorsport.

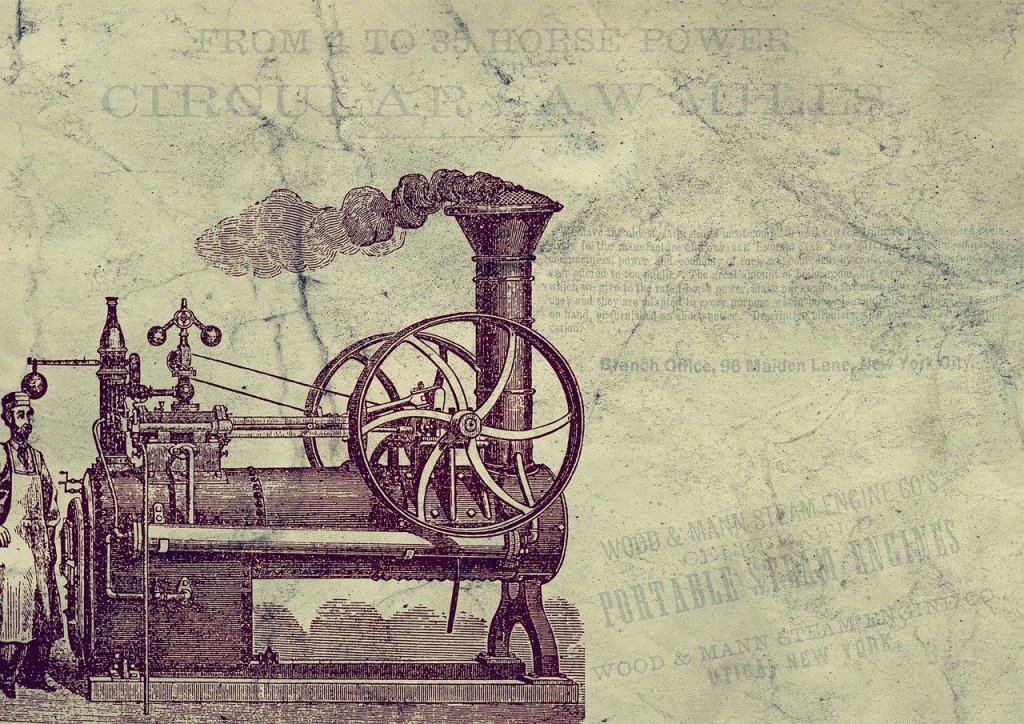

Consider further that the first ‘modern’ car (essentially a trike with an engine) didn’t materialise until the late 1800s, and you realise the blistering speed of the technological progress that’s led to the machines I’m glancing up at now. It isn’t just cars either- the time between the first powered flight and the Moon landing is a mere 66 years.

Aside from damning evidence I am influenced by my surroundings while writing, this is a long way of showing that both a key symptom and, fittingly, driver of the industrial revolutions is transportation.

Having gone thousands of years without, in only a short time we can now travel over, under, and above land in a plethora of ways. The zone between A and B has never been so inundated with options. Humans have never moved so much in so many different ways. It’s made us more sedentary than ever.

Living in a world wherein car dependency is widespread, and the need for our own two feet is defunct, is of course just one of the factors fuelling the obesity pandemic. Yes, a pandemic. Contrary to the common understanding the problem is localised in Europe and America, the World Health Organisation are keen to point out that obesity is a global issue (the usual suspects of the UK and America are surprisingly far down the list of highest obesity rates globally; Oceania dominates the top spots).

Thanks, in part, to transportation proliferation, health and fitness simply isn’t as necessary or valued now as it has been in history. In modern, developed society we don’t seemingly need to be physically strong and fit anymore for the most part. Modern life and medicine has allowed us to detach ourselves from nature’s demands in the animal kingdom, where fitness remains of vital importance for survival.

Even where fitness is promoted and championed, it is often entirely unrealistic. The unattainable forms of bodybuilders and models, that we use as our ungraspable yardstick, are a 20th century phenomenon and not historically the benchmark at all. This has heavily warped our view of what it means to be fit and healthy; these extreme examples of bodies are presented as being requisite to achieving health and fitness (they aren’t).

The oh-so natural reaction to this in our society is to make an industry out of it. And so it is that the stick dangling the unreachable carrot is held by the booming fitness industry. Some of the most damaging players here are the social media fitness gurus. Fakery, dangerous dieting, and bogus biology abound as these impersonal trainers prattle about their ‘fitness philosophy’.

That last point is perhaps where they are almost onto something. To escape the churn and burn perpetuated by the fitness industry we need to look backwards, understanding how we got here and realising that the answers to our questions and needs were lost along the way.

Immersing ourselves in the philosophy of fitness is a major part of this. Unlike the motivations and standards we struggle today to even begin working towards, philosophy is, by design, accessible and understandable for everyone.

Under our overarching banner of ‘fitness’ we will here use our Selfish History approach to uncover history’s toolkit. Shunning modern standards and motivations for fitness, I hope to show how history can equip us with the contextual information as to how we got here, the correct mindset, and the healthy dedication required to fulfil your fitness goals.

We will come knocking on the timeline all the way from early man, to ancient Greece, to the 20th Century in our pursuit of understanding how we lost our affinity for fitness- how we lost touch with our very nature.

Leave a comment