Can you tell me the name of your Great-Great-Grandfather?

If (like me) you can’t, you are complicit in the understanding that we are completely forgotten well within five generations of our death. In other words, as our family trees grow taller the upper branches are pushed above the cloudline and out of sight and memory.

A natural defence here is to think maybe we can be remembered if we perform particularly good (or bad) feats, or produce lasting wisdom that will forever be synonymous with our names. To that, here is a pertinent quote I found while researching this series:

They say we die twice – once when the last breath leaves our body and once when the last person we know says our name.

– Banksy

Well said Banksy. Or was it Ernest Hemingway? No, it was definitely Al Pacino. Actually, I am pretty sure it was Marcus Aurelius…or Irvin Yalom.

This isn’t even all the names I saw credited to the quote above. It serves as an example that while we can produce an acorn of wisdom that might in time become a great oak, eventually it is only the tree that is remembered- not the planter. The same is true across history.

Few now remember Vespasian, Titus and Domitian when they visit and stare in awe at the Colosseum in Rome, even though it was built under their emperorship(s). This is further apparent when you consider that the original name for the building, the ‘Flavian Amphitheatre’, was given after the dynasty of the three emperors. It was Nero parking an obnoxiously large statue (or colossus) of himself outside that gave us the name Colosseum as we know it today. While the statue does not survive, the name stuck.

The result is that, now, successfully crediting the generational project and legacy of the Flavians to their name has become a matter of trivia. Perhaps Banksy should take a leaf out of Nero’s book and produce a statement piece outside Al Pacino’s home, in the aim of cementing ownership of the fought-over quote we began with.

Numerous examples of this exist in history (the Great Pyramid was built by a chap called Khufu, and many tourists probably don’t know they are looking at his tomb) however it is still apparent up to the 21st Century. When did you last think of Steve Jobs when using your Iphone? Or, since his death in 2018, lent a thought to Stan Lee while consuming the latest output from Marvel?

While so many have left behind so much, personal legacy is a fragile, ephemeral thing and it is perhaps folly to try to expect our names to carry through the ages- only very few have succeeded and will succeed in this feat. I believe the second life that Banksy et al refer to begins straight into life-support. Perhaps it is more a countdown than a rebirth.

Of course, you may think it egotistical to need your name remembered alongside your achievements, and instead be content to simply leave this place behind better than you left it. This angle, and practical steps to succeed at it, will be discussed in the series also. It is these applicable-to-us learnings from history are directly in line with the Selfish History ethos.

So, yes, in this first series we are naturally getting ahead of ourselves and starting at the end. Legacy is a topic which is simultaneously important to one person but utterly insignificant to another. It can proudly cap off a life’s work, or go unconsidered and disregarded to no regret or suffering for the individual concerned. Legacy has long found itself under the microscope of historians and philosophers alike, and we will over the course of the series visit a selection of the angles and examples on offer to us.

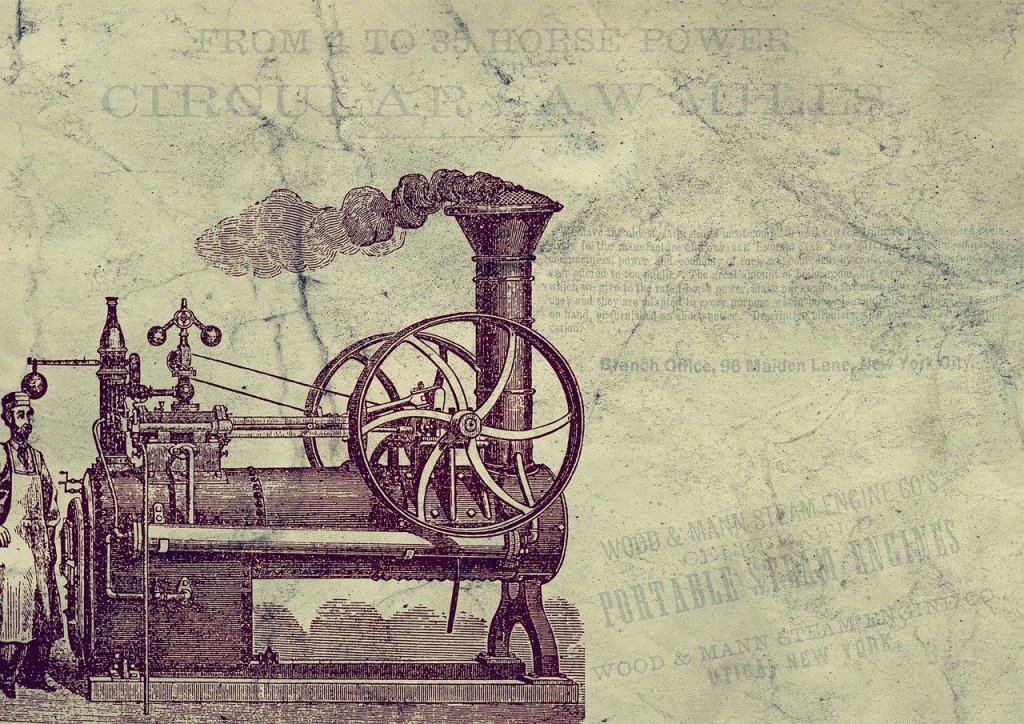

The idea of legacy itself, to me, harks to an earlier time and to broad ideas and cultures. We hear of the legacy of Rome and the legacy of colonialism. If I spent my entire working life in the 1800’s toiling away in the engine room of a steam train, am I to be satisfied that my legacy is bundled into that of the industrial revolution? Or, worse still, the culmination of my years-long hard work in the mines being quelled and assimilated into the legacy of Thatcherism.

This speaks to the ethos of Selfish History, where we look deeper than the broad strokes of history to find personal meaning and value- uncoupling from the widely touted takings from history we understand, but cannot apply in our own lives.

Nowadays we hear of ‘legacy corporations’, products and brands which are much-beloved for generations. For a product to have a legacy further muddies the waters of defining the term, and speaks to the contortion of capitalism we are now seeing. Many are now refusing to have their legacy entwined with their careers. We don’t wish to have ‘facilitated a 30% rise of sales in financial year 2024’ on our gravestones. This hasn’t stopped Linkedin offering an option to memorialise yours or a loved one’s account to ‘allow a person’s legacy to remain on’ the platform- long live your sales record!

No, instead we want to be remembered for our personal lives (‘caring father’ or ‘loving mother’) and accomplishments (‘dedicated charity ambassador’ or ‘record holder for the steak and ale pie eating challenge down the local pub’).

History throws up all kinds of examples of people trying, with varying success, to forge their legacy. These are so often the Alexander the Greats (subject of part one) of their time. Those with an inherited familial legacy to uphold, a duty to add something of value, and- most importantly -the tools and status with which to stand a chance at being remembered past five generations.

We will also take a look at the smallest of legacies in history, people who have left behind some slim scrap of evidence they ever existed, which we can use as a launchpad to discuss some big questions. Important to remember throughout is that the vast, vast majority of humans in history are of course completely forgotten.

Does this highlight the futility of caring about legacy for the average person, or in fact underpin the importance of living well for the right reasons? Does legacy only matter for the big names, or is it even more important and impressive for us to live with virtue despite knowing we will be lost to the murky waters of time?

Perhaps we have no control over our legacy whatsoever, or our legacy is at the mercy of shifting cultural attitudes and our own characteristics. In the context of a decrease in theism globally, does legacy even matter at all- we will, after all, be dead and buried.

In Selfish History style, I hope this series helps you to understand about what you want to do, if anything, about your legacy. This is learning from history for those of us who can’t fashion a wonder of the world to be remembered by, although, as we will find out, that entirely depends on your definition.

***

Oh, you’re still here because you want to know who out of the lineup of suspects actually said that quote earlier on.

Ask yourself: does the source matter more, less, or the same than the preservation of the quote itself?

The answer might be a useful way to reflect on your own views on legacy.

Leave a reply to Peeling back the ‘Great Man Theory’ to reveal the undervalued legacies of history’s unsung women – Selfish History Cancel reply