Hedonism is generally defined as the pursuit of pleasure, often realised through self-indulgence. It is however also a philosophical way of life – locating ‘the good life’ in the cultivation of pleasure and, therefore, the absence of pain.

It is a definition, and controversial lifestyle, that has been applied to infamous rulers in history, giving hedonism a poor reputation and relating it to outlandish, unrelatable and almost fantastical elites. Here we will visit two famous historical hedonists before looking deeper into its philosophical roots, discovering complexity that extends beyond historical embodiments.

Lastly, we can apply this greater understanding, with use of a modern stem, to reconfigure our approach to fitness and find personal value in a pursuit which has been historically maligned.

The Puritan Prude vs the Merry Monarch

Oliver Cromwell isn’t known to history as a pleasure seeker.

The Interregnum (1649-1660), of which a significant portion Cromwell spent as ‘Lord Protector of the Commonwealth’, saw subjects given the treatment of republican governing. This course of treatment was not without a healthy dose of Puritanism, administered by Cromwell and others, looking to drive out decadence and excess in favour of nurturing an austere and pious society.

Cromwell’s most (in)famous measure is probably the banning of Christmas and Easter celebrations. However, while the elves and bunnies were indeed relegated to the workhouse queue, numerous other measures were written and delivered by the Puritan Pen.

Generally, if an act or institution encourages enjoyment for enjoyment’s sake, then it isn’t part of Cromwellian doctrine. Theatres, inns and sporting activities were all banned or heavily regulated and shaped into Puritan friendly imitations of themselves. Personal expression was further diminished through the requirement of plain dress.

Naturally, by the end of his life, Cromwell didn’t curry a great deal of favour in England and beyond. His death precipitated events (including the failure of his son Richard to maintain the protectorate) culminating in the return of monarchic rule. The contrast between Cromwell and Charles II is a rather wide cultural canyon; Charles’ return to England from exile symbolised a return to hedonism at the top of society.

Under Charles’ French-inspired approach to life at court and his hedonistic hand, doors of theatres and inns were flung open once more. The legacy of Cromwell was deconstructed one raucous evening at a time, the ghost of his republic in the Whitehall corridors blasted away by a shockwave of courtiers and mistresses.

Clearly we are focusing solely on one aspect of Charles’ reign of 1660-1685, however his widely understood status as one of the most hedonistic monarchs in English history is what he is largely synonymous with. Indeed a generation in the UK will know him as the ‘King of Bling’. (He was also contemporarily called the ‘merry monarch’).

It is likely accentuated by the contrast of Puritan life in the Interregnum, but this period and its figurehead solidify the notion that some rulers are defined in popular historical knowledge by their hedonism and party animal status. A symptom of this is to take a rather simplified view to hedonism as a philosophy, obscuring the approachability, complexity, and value in this system behind a veil of wild rulers and the flamboyant elite in their posse.

We can work our way back to the root of understanding the varying types of hedonism, and follow it up to the most modern branch which can improve our approach to fitness, through visiting another high standing hedonist: Caligula.

Caligula – Happy in the Haze of a Drunken Hour

‘Caligula would have blushed’ at ‘What she asked of me at the end of the day’ according to Morrisey of the Smiths. He ‘would grin’ at the antics that the band known as Tool got up to in their retrospective song ‘Invincible’. Caligula (ruling AD 37 – 41) has become something of a byword for hedonism – as well as debauchery, excess, perversion, and tyranny – in recent times, his name appearing alongside Nero and Commodus in lists of Rome’s worst emperors.

By most accounts Caligula’s, or, to use his actual name, Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus’, initial grasping of the imperial reins was a smooth, popular accession. The Alexandrian philosopher Philo, as part of an embassy from his home city, met Caligula in 40 AD: he described the first act of this theatre-loving ruler’s reign as a ‘golden age’, emphasising his acclaim empire-wide.

While perhaps Philo concentrates or embellishes on the positive in order to butter up his diplomatic target, this positivity is corroborated by Suetonius in his multi-biographical historical work known as ‘The Twelve Caesars’. Here we read that much celebration was indeed to be found in the first few months of Caligula’s taking of office.

However, this could, says Suetonius, be attributed to inherited favour from his popular father Germanicus as well as in response to the change from Tiberius, who has become quite unpopular by the end of his life. Either way, the formation of Caligula into the mad and hedonistic emperor we know him as today soon took place following the aforementioned calm before the storm.

In a similar mould to Charles II, operating more than 1600 years later, Caligula indulged deeply in arts and games, deriving pleasure from theatrics and, often, from the pain of others. Soon he would take lives (civilians, senators, and consuls in various manners), wives (bedding whomever he pleased, even on their wedding night) and, famously, the mick when he potentially sought to make his horse consul.

Modern historians have casted doubt on the extent of Caligula’s tyranny and attempted to add complexity and balance to his one-dimensional character. This apologism has been performed to varying degrees of success (although it does represent the importance of viewing sources beyond face-value), however it has not liquified the cemented character of the man himself.

Instead, Caligula’s image has only been made more defined by his popular understanding, bolstered by the winking contributions to him made by the likes of the Smiths. It is this synonymousness with hedonism that paints the term on a canvas as one-dimensional as its frontman and so, with a brief historical understanding complete, we can delve beyond the surface of this philosophy.

Hedonism: More than Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll?

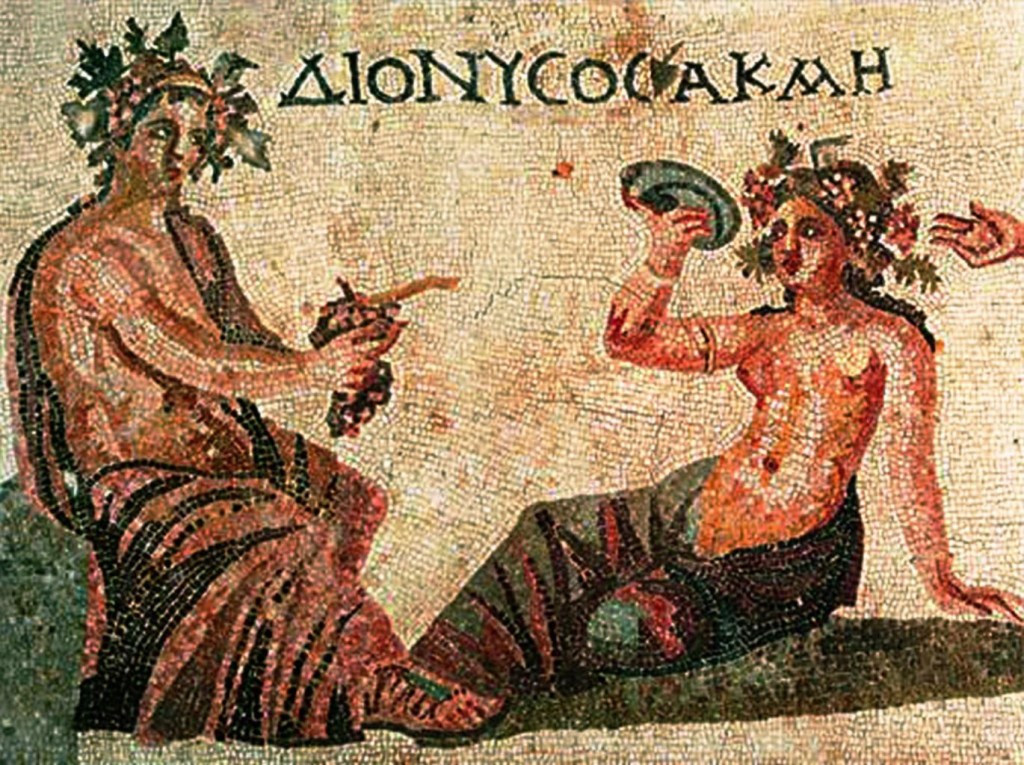

When the gods of love (Eros) and soul (Psyche) become parents, it is a safe assumption that their offspring will enter a career peripheral to the family business. Their daughter Hedone, goddess of pleasure, thus fittingly gives her name to Hedonism, and is the mythological founder of this way of life.

The tangible, historical formation of hedonism, contrary to its cultural understanding, is however embedded in serious philosophy. Naturally it starts in ancient Athens and, typically, with a student of Socrates: Aristippus of Cyrene. Aristippus was however something of a black sheep in the Socratic herd.

Socrates’ enjoyment for wine, parties and attending symposiums piqued the interest of Aristippus, who decided this aspect of his master’s life was to form his own philosophical thoughts. It is in this way that the pursuit of pleasure, especially present, bodily pleasure was forged by Aristippus into its own philosophy of life: Hedonism.

Contrary to modern representations and historical examples of hedonists, Aristippus stressed greatly upon the importance of control and moderation in achieving pleasure. Unlike Caligula, Aristippus poured effort into remaining the master of his quest for a life of pleasure, striving to avoid becoming subjugated by that he utilised to generate pleasurable sensations.

It is this importance placed on control that underpins his most known quote: ‘I possess, I am not possessed’. This respect for oneself also, under hedonist teaching, extended past exploitation: Aristippus forbade the cultivation of pleasure through inflicting harm on others.

Despite the other side of the hedonist coin stressing moderation, self-awareness, and even altruism – Aristippus recognised the value in helping others to create pleasurable feelings for all concerned and Altruistic hedonism is an important part of holistically understanding the wider philosophy – this failed to convince Aristippus’ contemporaries or prevent his eventual expulsion from Socratic schooling. It’s alright though, Arristippus started his own school: the Cyrenaics.

A useful way to further understand Hedonist teachings as tutored in the Cyrenaic school is to compare to how it differs from the, often more widely understood, philosophy of Aristippus’ contemporaries.

For instance, Plato distrusts the senses in determining truth and knowledge, instead placing true wisdom as to be found in the metaphysical world away from the ‘hindrance’ of bodily senses. Hedonism contrarily brings the focus directly to these physical sensations as the well of value in life. Therefore, to Plato and company, hedonism functions to draw followers away from true knowledge in favour of (literally) surface-level sensual pleasures.

Further, Socratic philosophy generally places the pursuit of virtue above all, whereas the supreme good is found in pleasure by Aristippus’ judgement. These views are made increasingly disparate when one considers the temporal difference in achieving a good life: Aristippus identifies present pleasures (being in the moment) as the gold-standard, while this promotion of gratification differs from the lifelong pursuit of virtue and wisdom as undergone by Socratic students.

Hedonism is not to be found in the curriculum of numerous other philosophical schools. Perhaps the most antithetical position is taken by the Stoics. To Stoics, emotions are not in our control and are to be viewed indifferently – they are not objectively good or bad. And so hedonism, with its focal point fixed on the sensation of pleasure, angers Stoics (if only they succumb to a negative measure of the emotion!).

***

Aristippus’ Cyrenaic school fragmented in the decades following his death and eventually passed into the realm of textbooks, becoming a fruity alt to Socratic thinking but never taken as seriously. (This was closer to the time of his grandson, Aristippus the Younger, who may have been responsible for many of the elder’s achievements due to source conflation over time.)

The spiritual successor – Epicureanism – is generally deemed to offer a more enlightened form of hedonism. Epicurus (341 – 270 BC) flipped hedonism and added specificity to Aristippus’ Cyrenaic doctrine, which sported a paradox: the pleasure paradox.

This outlines that lifelong pursuit of pleasure is fruitless as we never achieve ultimate satisfaction, always chasing the next high in futile search of lasting contentment and happiness. Epicureanism outlines a more defined method of achieving long-lasting happiness.

Under Epicureanism it is not the presence of pleasure that is centrally pursued, but the absence of pain. Epicurus wasn’t about that stereotypically hedonistic lifestyle, instead advocating for a life of simplicity and tranquillity which, contrary to hedonism, searches for a deeper sense of happiness.

That said, hedonism has seen something of a resurgence in recent discourse: its broad philosophy has been moulded into application to the fitness industry. It seems a paradoxical enterprise (linking hedonism to an activity most equate with pain and suffering) but this ‘healthy hedonism’ holds a new way of looking at Aristippuss’ chosen lifestyle.

Harnessing the Hedonist Approach to Fitness – Healthy Hedonism

Hedonism and exercise might seem at opposite sides of the tug rope, with ourselves in the middle attempting to balance these two seemingly incompatible forces. For many who choose one side or the other, there is an impression that the other team are missing out foolishly: ‘life is about pleasure, not slaving away in the gym’ vs ‘exercise is the key to happiness and those who spend their life partying are wasting it’. It is a reductionist take and, in the case of healthy hedonism, needless.

Modern diet and exercise regimes are bundled with negative connotations including sacrifice, punishment, restrictiveness and an overall impression of forcing oneself through proceedings in hope of light at the end of the tunnel. The fact you must maintain this for a lifetime is inconsequential while in the depths of the latest exercise fad, a sapping realisation to those few who succeed that says the effort has only just begun.

Healthy hedonism recommends a sustainable approach to pleasure, in a manner that can be upheld and not impact negatively on overall health and wellbeing. In the context of fitness, we must strip away the view upon it as punishment.

Instead, we set about finding forms of exercise that enrich our lives and, channelling Aristippus, we can enjoy in the moment. Thus we enjoy not only the fruits of our labour, but the ‘labour’ itself.

Adopting a healthy approach to hedonism also places bouncers on the door of the pleasure pantheon. Short-term pleasures such as drugs and alcohol are dangerous mirages of pleasurable sensations, soon giving way to health issues and hindering long-term pleasure and happiness. Healthy hedonism promotes high quality and diverse pleasures such as intellectualism and physical exercise to add cement to the spaghetti tower holding up the wellbeing and pleasure of those addicted to their vices.

So, what if you flatly despise exercise and truly wish to live a long life of pleasure? It is possible that you should still consider picking up the dumbbells for a net gain of happiness.

A healthy approach to hedonism, contrasting Aristippus and Epicurus, recognises the value of a little pain. Pain as a gateway to pleasure – the ‘true creation requires sacrifice’ angle – necessitates exercise and upholding physical health for the diehard hedonists among us.

The pain endured through exercise is a facilitator to a longer lifespan as well the ability to extend pleasurable activities. Likewise, a little delayed gratification when it comes to our diets translates to greater overall health and longevity which equips oneself with the tools required to compound pleasure cultivation.

Overall, the healthy approach to hedonism encompasses the benefits of Cyrenaic and Epicurean teachings, while actively minimising the drawbacks that lend hedonism a bad name. Here we see a greater focus on moderation, a more narrowly-defined and sophisticated type of pleasure which promotes long-term happiness, and the introduction of a modicum of pain to our lives for the greater good.

For our fitness approach, if you don’t view exercise as a hedonistic activity already, it is recommended to find a form of pleasurable exercise, focusing on the long-term positive impact this will have on the achievement of a life full of positivity and uninhibited healthy pleasure.

Selfish History’s book recommendations:

The Birth of Hedonism – The Cyrenaic Philosophers and Pleasure as a Way of Life by Kurt Lampe

If you seek a deeper philosophical overview of the Cyrenaic way of thinking, and a more indulgent look at the drama of Aristippus’ temerity in disagreeing with Socrates, then this is the book. It’s a comprehensive and philosophical history of the formation of hedonist thinking which will raise your awareness of the benefits and pitfalls in adopting this approach in search of the good life.

The Art of Happiness by Epicurus

The above work focuses only on the Cyrenaic school, not including the more refined Epicureanism. So, why not hear it from the horse’s mouth? This book gathers much of the words of Epicurus in his life, offering an overview of his lasting philosophy. In the least, it refutes and challenges much of Stoic thinking (of which you are more likely to be well-read), and so serves to introduce balance and an alternative approach.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply