DISCLAIMER: I am not a financial advisor. (Or historian, or philosopher – but we can gloss over that I’m sure.)

I haven’t a Cluedo: Reluctant Players

‘I don’t bother with any of that’. ‘It all means nothing to me’. So common are responses such as these groaned from people even hearing the words (or associated) ‘stock market’ that you would think it an entirely unreachable entity, shrouded in quantitative voodoo.

At first glance, its heavily graphical blurb doesn’t inspire one to open the book – especially if, like me, you aren’t particularly numerically minded. A perceived lack of approachability is enough to turn off most from engagement with the markets and translating this into any financial benefit (which can be life-changingly great).

Some might also be put off by historical crashes, although I hope to flip these around as an inevitable phenomenon that can even be welcomed by the sensible investor. The wider reality is that we need not be so inexorable in our refusal to even attempt to engage in the world of investing.

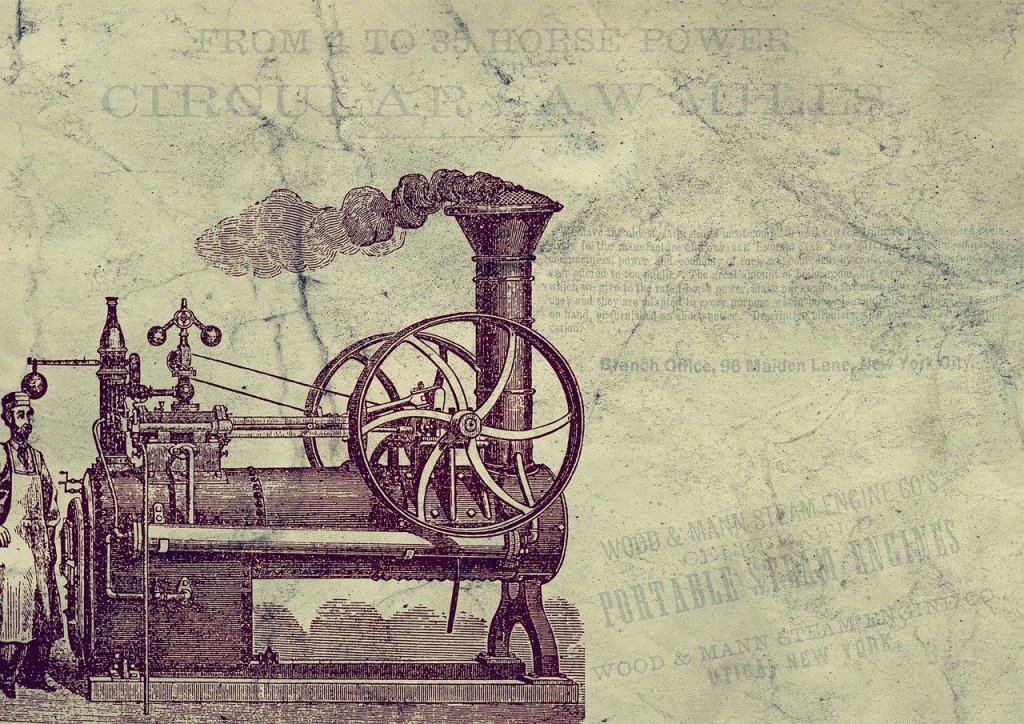

Never has investing been so accessible and affordable for us Joe Public; gone are the days of the privately educated monopoly on investing, though perhaps the cloud is still clearing for many to see entry is now rendered accessible. However, for the purposes of this discussion we are required to understand why public schooled men shouting supposedly made the wheels of capitalism turn.

So I thought, perhaps, it is best to start from the start. Holding a historical understanding of the workings of stock markets provides the very definition of foundational knowledge. (If you are already clued up on investing lingo, the history remains pretty interesting regardless.)

It all began with spices, opportunistic sailors, and the world’s first multinational corporation.

Battleships in the 17th Century: a Game of Dutch Dominance

In the early 17th Century, water kissing the port of Amsterdam’s walls did so upon those of a, if not the, global economic power. Sailors could reach this journey’s end from any one of the new canals sprouting up around the city. These waterways now tendrilled Amsterdam’s layout like bodily vessels: launching ships outwards to the world, then welcoming them back – sitting heavier in the water – sporting the gilded lustre befitting of a voyage well-made, and a sign of the anticipation of prosperity from sales to come.

Gilded perhaps is the whole country. This is, after all, the Dutch Golden Age.

Such a meteoric rise, occurring in but a handful of decades, surged in the early 1600s with a realisation that is simple to explain, yet arduous and daring to uncover. While only one factor in facilitating the Golden Age, it represents a key differentiator wherein previously established powers fell on the wrong side.

***

To access the immeasurable wealth associated with the spice trade one must take on the Indian Ocean. Portugal’s route, the very same copied by others (including the Dutch), was the convention of the day – and served Lisbon-based vessels well.

For this route, we can thank (or at least acknowledge) controversial Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Captain and crew sailed past the tip of Africa in 1497 and continued to hug the coast of East Africa via the Mozambique Channel. Using India as the final steer, empty pockets and stomachs arrived in the lucrative East Indies.

In successfully traversing the Cape of Good Hope, da Gama joined the Atlantic and Indian Oceans in a union of globalisation. This single journey precipitated the rise of European imperialism and granted Portugal an effective monopoly on the bounty previously concealed by Africa’s great landmass.

That is until 1611 when Dutchman Hendrik Brouwer sailed south from the Cape, and rode the prevailing winds straight across the Indian Ocean. The Brouwer route halved the voyage to only six months. Game on.

Portugal, the epoch defining force of the Age of Discovery, were now outwitted and outdone. The Brouwer route (literally) across the maritime battleground of the Indian Ocean had swung the game wildly in the Dutch’s favour. The superior route to dominance in the East Indies lay open, and the winds of colonialism now blasted Dutch sails.

It is one achievement to discover the potential of grasping the spice trade, but quite another to make it tangible. The Netherland’s newfound position of navigational power in this region surely required a highly organised outfit, primed to cram the Brouwer route like industrious worker ants. Such an enterprise would take years to materialise. Luckily they already possessed one, which we shall get to.

The Brouwer route, while significant, is but one blow to the European powers such as Portugal. For a wide variance of reasons, the Dutch blueprints to maritime empire building excelled in comparison to others.

Europe Scrabbles to Retain Power

Despite their first-come-first-served entry to the age of discovery, diminished in this period are the powers of Spain and Portugal. Their disproportionate focus on the Americas and their misplaced efforts for religious conversion were hindrances in establishing lasting overseas empires flourishing with trade. Portugal, of course, also lost their navigational advantage.

French merchants, meanwhile, were too constricted by the crown’s grasp on mercantile trade and dominion over profits, offering limited chances for opportunistic or organic growth. Britain, while nipping at their heels, are yet to mount a true challenge to the mercantile supremacy of the Dutch; the Brit’s empire is not to reach its apotheosis for hundreds of years yet.

The Dutch model, clearly, had something that other European powers did not implement to their approaches. They applied a corporate, capitalist sheen to colonialism, enacting a power dynamics shift that would change the face of economic history. It’s the reason I can go on my phone right now, navigate to the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, and become a shareholder in, let’s see, Heineken for some €80.

The Jewel in the crown of the Golden Age empire was the Dutch East India Company (VOC): the first multinational company and the first (as we shall get to) publicly traded company in the world.

(Note: While I refer in places, I haven’t the scope to cover all the evil and criminal activities of the VOC. Refer to these links for a deeper overview – and do your own research if you wish – but bear it in mind we aren’t talking about a company that would pride itself on its robust corporate responsibility program.)

The Dutch East India Company’s Commanding Monopoly

Looking at a density map of VOC shipping routes shows just how extensive Dutch tentacles reached at this time. (The thickly-laid veins from coastal west Africa to Amsterdam is one of those implicit but profound representations of atrocities, laced with hinted dread of the lives carried along a what is here a simple mapped line.)

The Dutch in the name is more of a descriptor than a possessive; this organisation had its own powers to enact war and establish governmental agreements. The Company could even strike its own coins as part of its sovereign powers. This separation from the far-away west put the power of decision in local, knowledgeable hands and transformed imperialist management practices.

It is here that we can understand the formation of the first stock exchange. Merchants, being separate from the Dutch governing body, began to raise funds from investors for their voyages. In fact, the VOC as an entity offered shares publicly, paying a major dividend (annual payment) of up to 40% to those who invested in its lucrative spice trade monopoly.

To centralise, organise, and allow profit to be maximally accessible the Amsterdam stock exchange was opened for trading alongside the formation of the VOC in 1602. The relationship between company and exchange is a nice way to illustrate the basics of security trading (which is just as well, because VOC shares were the only available for a long time).

Stock Picking: a Trivial Pursuit?

Picture all the individual ships of the VOC, each vying for success and investment. Together, they form what we shall call the overall market. The question facing us, the investors, is which ship, or stock, to put our backing behind.

Perhaps we could inspect the crew, research the captain, or poke around the rigging. We certainly don’t want to back the ship that looks likely to sink spectacularly upon rocks barbed with financial loss. These naval age considerations have equivalent contemporary aspects that millions of investors look at today: revenue growth, price-earnings ratio, dividend growth.

Surely, if you think that generally speaking most ships will enact a moderately successful voyage, it would be easier to invest in every vessel. Today, you are able to do exactly that thanks to an investment security known as an exchange-traded fund (ETF).

ETFs function as a basket of individual stocks based on an underlying index. Here we invest in the shipwrecks and the glorious successes, on the understanding that the average holding will be a positive one.

ETFs allow the investor exposure to hundreds of companies at once without the concern and volatility that can often strike individual picks. The index that many may have heard of is the S&P 500, which tracks the 500 biggest companies in the US by market share.

However, an even wider net can be cast through the availability of global ETFs which cover thousands of securities based on market capitalisation. A pleasing way of viewing this pooled investment is you can’t lose to the market if you are the market.

Game Over

So it is, then, that the Dutch method of imperialist expansion was the foundation for the first stock exchange. The beginnings of what we now call globalisation in this period can also be traced all the way to today’s global ETFs, which allow investors to form an instant set-it-and-forget-it diversified portfolio.

The journey from the first publicly traded stock to today’s digital exchanges housed in our devices is a long and arduous one. In many ways, the story of human development can be told through the peaks and troughs of global markets. That is a saga for another time.

I suspect that a great many would-be investors believe they need to spend time inspecting ships and constantly reassess their stock picks based on specialist information. If so, it is worth stressing that buying the whole fleet is a very accessible option.

Selfish History’s Book Recommendations

In acknowledgement that the above is split into two distinct areas, and in the spirit of Selfish History’s dual-approach, here is one historical book and one financial one. Plot your route of further reading as you wish…

Spice: The 16th-Century Contest that Shaped the Modern World by Roger Crowley

As alluded to above, before the Dutch controlled trade through the Indian Ocean and surrounding regions, Spain and Portugal competed for supremacy. Narrative historian Roger Crowley (a personal favourite) here spins the totemic tale of the 16th century age of maritime discovery and global trade through placing the product firmly in focus: spices.

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: The Only Way to Guarantee Your Fair Share of Stock Market Returns by John C. Bogle

You may have heard of leading financial services provider Vanguard, but you may not know of this book by its founder: John C. Bogle. Bogle created Vanguard on the strong belief that investing in low-cost index funds (as we briefly covered above) is the smartest way to put your money to work, and the company offers many to investors worldwide.

Adherents to Bogle’s financial philosophy – Bogleheads – have a ‘bible’ of sorts in the form of this book. Few people can be credited with transforming more financial lives than Bogle, and his legacy continues.

A quote from the book related to our discussion: ‘Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!’

—————–

Investments can rise and fall and you may get back less than you invested. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Your capital is at risk.

(Basically, don’t come knocking with a lawsuit.)

Leave a reply to susieberesfordwylie Cancel reply